Transforming the Riverfront: A Hidden Piece of Cincinnati’s History

In the small city of Sedamsville, situated between the Ohio River and a major railroad, stands a terminal with a rich industrial heritage. For decades, this site has played a pivotal role in the region’s infrastructure, serving as a key logistics hub due to its unique access to river, rail, and road. At its peak, it moved more freight than the Panama Canal — a remarkable figure that speaks to its significance.

Today, this site is known as South Terminal, part of CREMER North America’s Cincinnati campus. It’s easy to overlook the decades of transformation that have taken place behind its walls. Though, for Mike Doll, who’s been with the plant through its highest peaks and toughest shutdowns, every pipe, tank, and hallway tell a story.

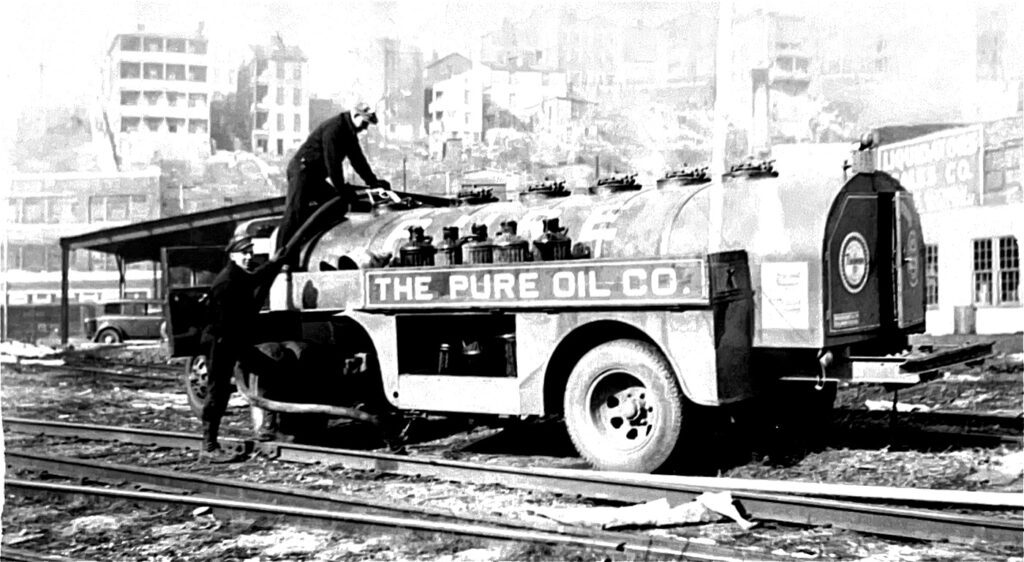

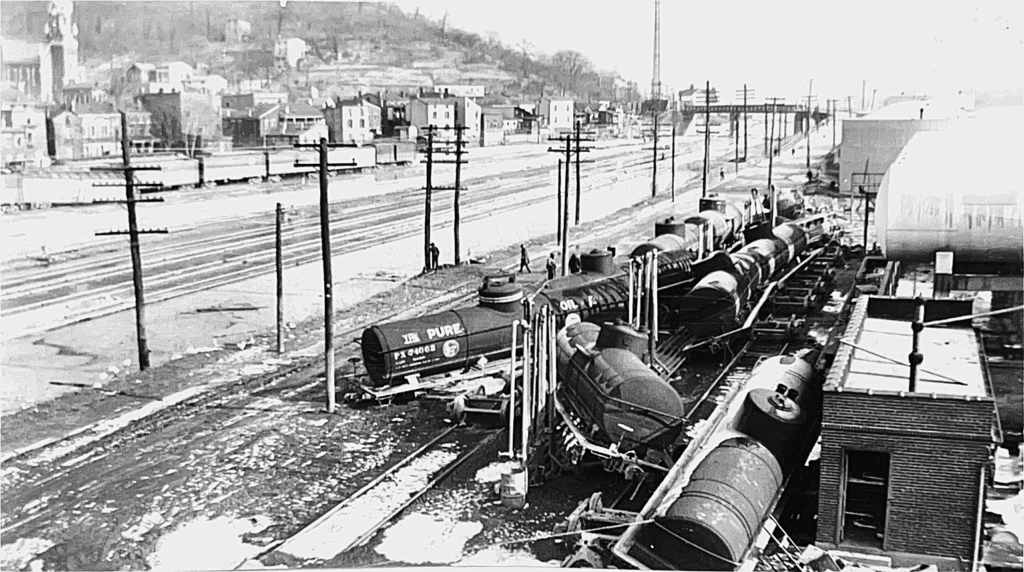

A Beginning in Oil

Before the City of Cincinnati annexed Sedamsville in 1870, the town was small, with only about 40 buildings lining River Road. As industry began to take over the region, the city’s population grew alongside the arrival of factories and commercial activity. However, the neighborhood later faced major challenges, having to endure the Great Depression, the devastating flood of 1937, and the widening of River Road in the 1940s. For many years, Sedamsville suffered a great decline in its business district, until some big players in the oil industry came along.

The history of South Terminal started in 1929, when the site was part of a major oil company. It remained solid for several decades, playing a key role in the region’s industrial development. In the 1980s, however, the company was on the verge of a shake-up: its investor was plotting to buy and dismantle the company for profit. To stay afloat, South Terminal’s then-owners merged with a major Venezuelan oil and gas corporation.

Mike, who joined the site in 1989, recalls that despite a lucrative merge and a spike in stock prices, the company’s success was unfortunately short-lived. They went bankrupt, and its new owners favored a Chicago refinery over the Sedamsville site, resulting in the shutdown of South Terminal’s operations. Of the 38 employees on-site, only four were kept on. Mike was one of them.

A Second Chance

With the plant shut down, Mike and the former maintenance manager were asked to come back to the site. They were instructed to prepare the facility for someone, though at the time, they had no idea who it would be. Mike recalls that there were numerous attempts to purchase the plant, noting that a major oil company was even considering buying the site and all the surrounding land. This deal, along with many others, fell through.

Eventually, a team of buyers in the oleochemical industry came along to visit the site. They were impressed by the facility and its strategic location. To them, South Terminal’s long-term potential was undeniable; so, without hesitation, they decided to purchase it. Mike, who knew every inch of the facility, was asked to stay on. “I came with the building,” he jokes, “I knew the facility inside out.” It was then, in 1999, that CREMER Holdings purchased CREMER North America.

Challenges and Lessons

The transition from petrochemicals to oleochemicals took months of hard work. Mike personally cleaned every single tank, calling it the hardest job he’s ever done. But slowly, the plant was reimagined, and the place came back to life.

When asked about the most significant milestone of South Terminal, Mike mentions two things: flaking and Kosher regulations. Flaking, which transforms solid fats and oils into thin flat sheets, required entirely new equipment and processes. There were moments of pure hustle, like the night that Mike, his son Mike Jr., and Troy Holbrock worked straight through to completely overhaul the piping and flaking systems. As for Kosher regulations, Mike admits it was hard to understand at first.

Kosher dictates which foods are permissible and how they must be prepared according to Jewish Law. “Learning the rules and maintaining a Kosher line was challenging to learn,” he reflects, “but throughout the process, I was able to build a great relationship with the guys and the rabbi.” Earning and maintaining key certifications became a core part of the transformation, reflecting the high standards the team set for themselves.

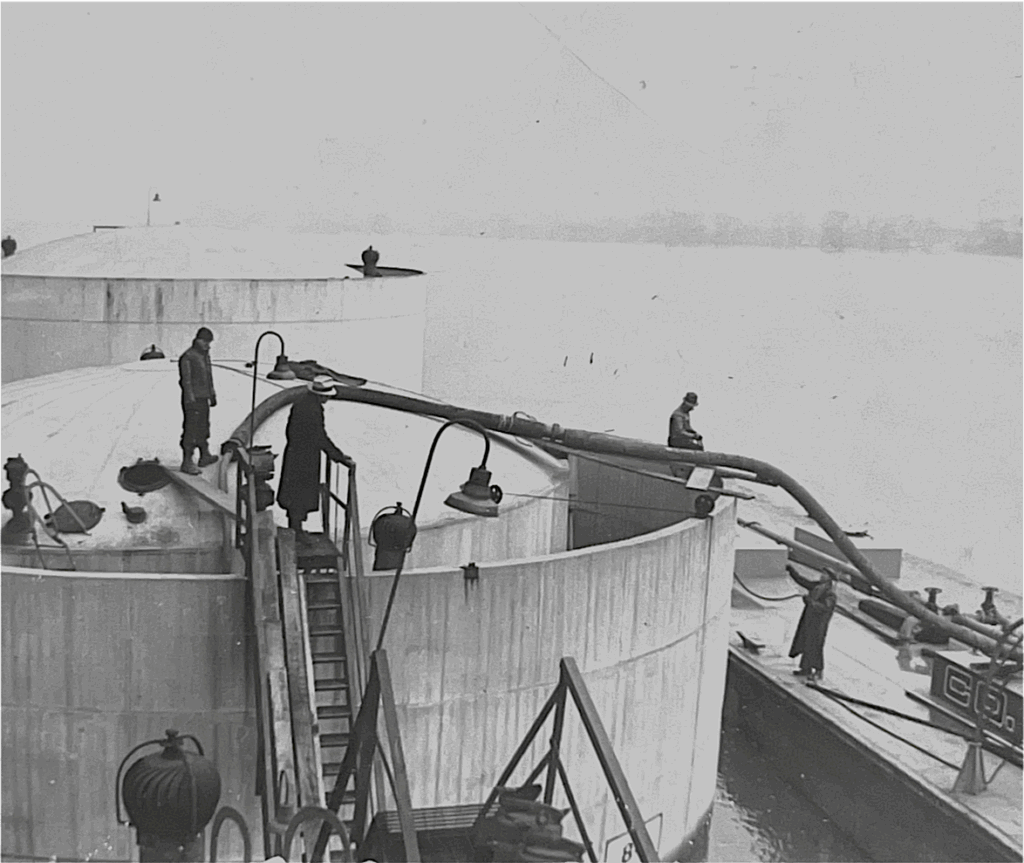

In addition to those milestones, another piece of South Terminal’s identity is its work float, named in Mike’s honor. Built in 1929 from a converted liquid barge, the float has been in continuous use for barge offloading ever since. It connects to three dedicated lines leading to the west tank farm and can be maneuvered using upriver, downriver, and breast cables, allowing safe operations across a wide range of river levels, up to 55 feet. The float is one of the few of its kind in the area and continues to play a critical role, offloading two different products and handling around three barges each month. What began as a simple loading platform has evolved into a symbol of South Terminal’s adaptability and long-standing connection to the river.

From installing the first belt to nearly being flooded out, the plant has been through its fair share of challenges. But through those trials, something deeper took root: a culture of resilience, trust, and pride. South Terminal became more than a plant — it became a tight-knit community. People looked out for one another. They worked late, problem-solved together, and built something that felt personal.

Community and Culture

The culture in place today didn’t come easily. In the early days, the environment was challenging, and the company initially struggled to find people. Mike saw potential in the ‘youngins’, so he brought in a lot of high school graduates. He can name many people who have inspirational stories, one of them being a young man, Troy Holbrock, who used to work at a pizza place and today, is CREMER’s Senior Industrial Maintenance Technician. CREMER has proudly held on to its goal of developing their staff and allowing them with opportunities to grow. “CREMER has been a great company for people to come and stay,” Mike says, “everybody has a chance to go up the ladder.”

Outside the company, South Terminal’s connection to the community runs deep. Mike served as co-op president, ran spill drills with the Environmental Protection Agency, and formed close relationships with fire departments and the Coast Guard. Once established, CREMER also helped raise money for Sedamsville and often gave back in small but meaningful ways, like taking the maintenance team to a Cincinnati Reds game or helping clean up the local roads and sidewalks.

When asked about his favorite memory, Mike still laughs about a call he got during a two-day plant shutdown years ago. After days with no answers, someone finally called him and said, “Mike, we figured it out! It was the flux capacitator!” Not knowing the reference, he passed the message along to Andy Aylwin, CREMER North America’s Co-CEO, before realizing he had walked into a Back to the Future joke. This was one of many moments that reflect the lighthearted and friendly culture that continues to grow over the years.

Looking Ahead

After 36 years at the plant, Mike still shows up every day, proudly wearing his CREMER shirts. “Mike is a wealth of knowledge, not only for CREMER, but in Cincinnati, especially in spill response and boom deployments,” says Stephanie Bailey, Barge, Bulk & Drumming Manager at South Terminal. “He has been a tremendous help to me and is a consistent resource when needed.” Though his official title is ‘CREMER Ambassador,’ Mike remains a vital part of daily operations. He’s regularly called upon for reference, plant knowledge, and pump or tank schematics.

“This place has been my life,” he says, “It’s about showing up, doing the work, and lifting others up with you.” This mindset continues to shape the team and operations not only at South Terminal, but also at CREMER as a whole. “There are some great things going on right now,” he says. “I hope to always see the parking lot full.”

South Terminal’s history has been one of constant changes across industries, ownership, and generations of workers. From its early days in oil to its current specialized production of oleochemicals, the plant has never stopped evolving. And it continues to be a place where hard work, knowledge, and experience drive what comes next.